Environmental responsibility continues to be a pressing concern for many, including researchers, policymakers, and the public alike. While the push for sustainability may seem relatively recent, it has been a significant topic of conversation for decades. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, for instance, first prompted critical conversations on environmental stewardship in 1962. Since then, there have been several revivals and demands for better practices.

Nearly sixty years later, Carson’s sentiments were echoed during the COVID-19 pandemic when the sudden decline in human activity brought about noticeable environmental changes. These changes reignited discussions on the importance of data-driven environmental decision-making. Fortunately, many researchers took advantage of this rare opportunity to assess human impact on the environment under entirely unprecedented conditions. This ultimately led to an influx of research publications that can now be used to better inform environmental policy and law.

One such Penn State-based research team capitalized on the empty streets in Indianapolis to study the effects of reduced human activity on greenhouse gas emissions, and they discovered surprising results.

Using Eddy Covariance to Assess Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions

In their July 2024 publication “Using eddy covariance to measure the effects of COVID-19 restrictions on CO2 emissions in a neighborhood of Indianapolis, IN,” Eli Vogel and coauthors sought to better understand the relationship between human activities and CO2 emissions—particularly in urban environments where fossil fuel use is more prevalent.1

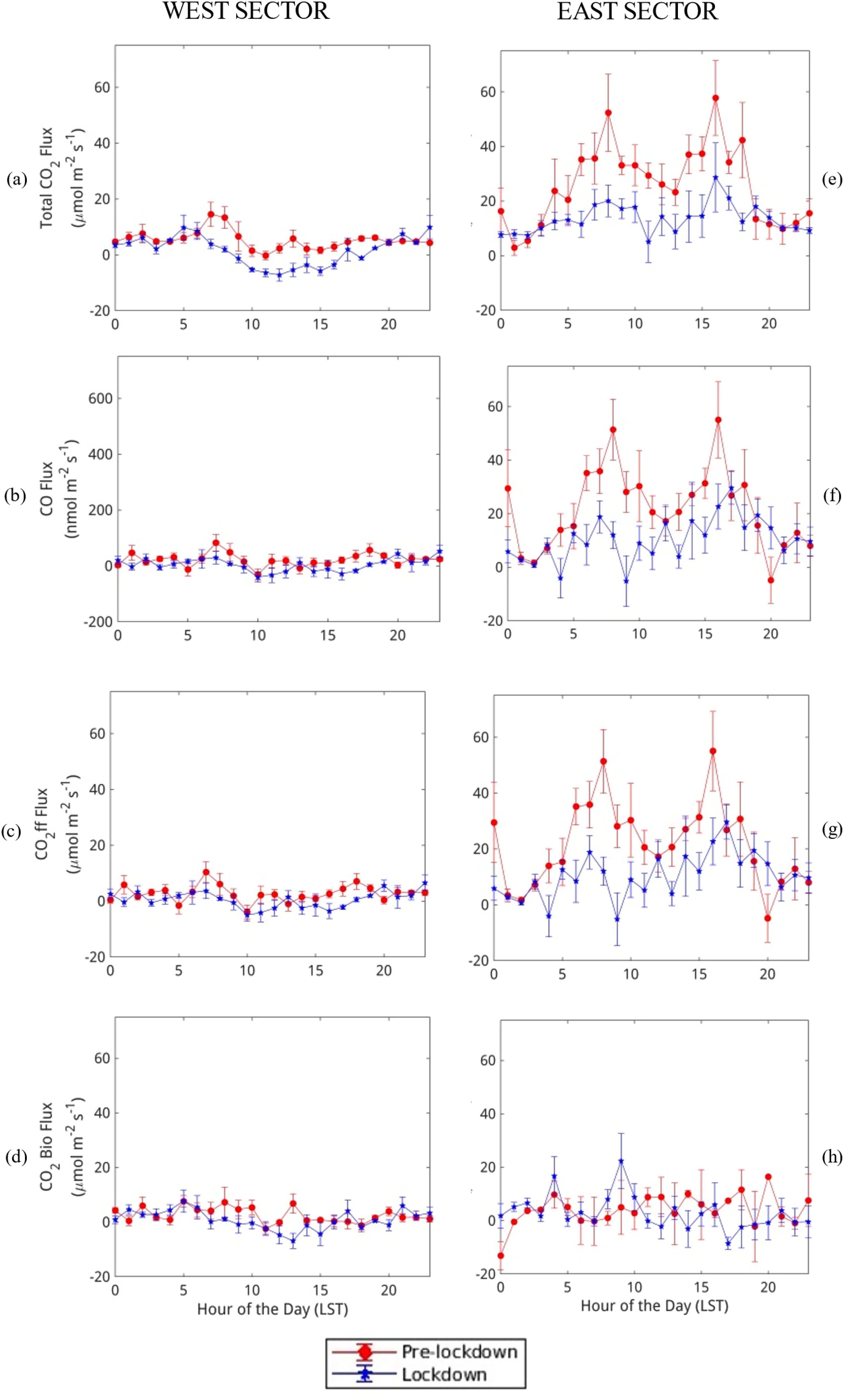

Leveraging the pandemic’s unique conditions, the research team employed the eddy covariance method—a powerful technique for measuring gas exchange between the ground’s surface and the atmosphere. An eddy covariance tower at the AmeriFlux site US-INg allowed them to observe emissions, depending on wind direction, of a highway to the east and a suburban neighborhood to the west over six-week periods before and during the COVID lockdown.

Fluxes were then calculated with EddyPro® Software, a robust open-source application that processes eddy covariance data for free. As the only processing software developed in collaboration with AmeriFlux and other leading organizations, EddyPro enabled the researchers to compute total CO2 flux results in real time and meet research submission standards with ease. They calculated fossil fuel CO2 emissions using total CO2 eddy covariance, CO2 and CO mole fraction measurements, and eddy diffusivity assumptions. Results were then compared to the 2020 Hestia inventory model’s fossil fuel CO2 estimates for both environments.

“I think using them in tandem was a great choice,” said Vogel. “The point of Hestia is that it uses inventory data directly from the source to estimate emissions. It helps us test whether our disaggregating method is doing what it’s supposed to be doing.”

The close alignment between the model estimates and fossil fuel CO2 flux data derived with EddyPro allowed the researchers to confirm and trust their findings. The study revealed a notable decrease in fossil fuel CO2 emissions from both the highway and suburban environments. The reduction appeared to be more pronounced in the eastern highway sector, which was more urbanized and influenced by traffic emissions; conversely, the western suburban sector was more forested and had less traffic.

However, the researchers acknowledge that other factors, such as seasonal changes, could have influenced the data. For instance, milder weather during the study period might have reduced the need for home heating and cooling, contributing to lower residential CO2 emissions.

“The data we had shows that general traffic was reduced significantly in Indianapolis during that time,” stated Vogel. “This suggests that traffic reduction was a large part of that drop in emissions, whereas the western reductions were much less significant. However, the reduction largely comes from a change in residential emissions, which could be from the change in seasons.”

Given these external variables, the Indianapolis FLUX Project (INFLUX) team recommends further research to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how temporary changes in human behavior affect greenhouse gas emissions. Larger, more in-depth studies could help determine whether these findings hold true over longer periods of time and under different conditions.

“What will be more relevant to future researchers and policymakers is to use eddy covariance data to study actual attempts to reduce CO2 activity,” said Vogel. “It would be a good idea to find opportunities to test for longer periods of time, too, and know for sure whether we’re seeing what we’re seeing.”

Relying on Research to Shape Environmental Policy

The INFLUX team’s research provides valuable insights into the direct impact of human behavior on greenhouse gas emissions. It also underscores the possibility that more permanent changes could lead to significant emissions reductions over time. Such research is critical for informing emissions mitigation techniques and shaping future environmental policies.

Photo Credit: Jason P. Horne, The Pennsylvania State University

In fact, research like this has been used to drive policy and law decision-making throughout history. The United States’ Clean Air Act, for instance, has used air quality monitoring data to inform new emission standards for industries, power plants, and vehicles in order to reduce pollutants. Similarly, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards, first enacted in 1975, called for more fuel-efficient vehicles and used scientific research to demonstrate the effect it would have on reducing CO2 emissions. The Obama administration updated the standards in 2012 using studies conducted by the EPA and DOT that indicated a significant correlation between vehicle fuel efficiency and CO2 emission reductions.2

As research like Vogel’s continues to inform environmental policy, it underscores the importance of scientifically backed legislation. Vogel himself is keen on this intersection between research and policy and is now redirecting his career toward environmental lawmaking.

“I’m pivoting toward policy right now and would love to work on local environmental bills,” said Vogel. “In undergrad, I minored in political science, so I’ve always been interested in the intersection of research and policy. In regard to the research paper, I think that experience will make it easier to ensure environmental bills are scientifically sound in the future.”

To learn more about this study’s eddy covariance technique and how it can be used in your own research, trust LI-COR to help. Our fully customizable eddy covariance systems are used by flux networks and researchers worldwide and are the most accurate and affordable on the market. EddyPro Software, along with other software options, can help you acquire, process, and communicate your findings with ease.

To learn more about the study, read Vogel’s publication for yourself.

References

- Vogel, E., Kenneth James Davis, Wu, K., Natasha Lynn Miles, Scott James Richardson, Kevin Robert Gurney, Monteiro, V., Geoffrey Scott Roest, Colette, H. and Jason Patrick Horne (2024). Using eddy-covariance to measure the effects of COVID-19 restrictions on CO2 emissions in a neighborhood of Indianapolis, IN. Carbon Management, 15(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2024.2365900.

- Whitehouse.gov. (2012). Obama Administration Finalizes Historic 54.5 MPG Fuel Efficiency Standards. Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/08/28/obama-administration-finalizes-historic-545-mpg-fuel-efficiency-standard.

Audrey Habron is a freelance and contract scientific writer in the environmental, biotech, healthcare, medical, and pharmaceutical industries. She has over six years of experience in scientific communication, digital marketing, and content management and holds a bachelor’s degree in biology. In her free time, Audrey enjoys exploring national parks, advocating for sustainability, and discovering new ways to merge her passions with her professional endeavors.

Audrey Habron

www.audreyhabron.com | audreyhabron@gmail.com